In recent decades, Brazil has made significant progress in reducing poverty and inequality, mainly by implementing and consolidating nationwide social programs. Economic growth in the ’90s and 2000s, fuelled by favorable commodity price trends, allowed the country to establish large-scale cash transfer programs, responsible for lifting approximately 30 million people out of poverty.

Social policy is considered an essential component of the recent Brazilian model of development, along with economic growth and the political consensus that characterized the first decade of the Lula administration (2003 - 2011) (UNU-WIDER 2014). Since 2003, most of the federal government’s social programs have been consolidated into Bolsa-Familia, a comprehensive Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) program providing basic assistance to ~50 million citizens - over 25% of the Brazilian population. In 2011, the Brasil Sem Miséria (Brazil Without Extreme Poverty) program was launched, with the ultimate goal of eradicating extreme poverty in Brazil by 2015. Brasil Sem Miséria is currently the official umbrella federal social program, encompassing Bolsa-Familia and several other programs under three main pillars: minimum income guarantee, access to public services, and capacity building.

From 2003 to 2011, Bolsa-Familia was the landmark social program in Brazil, and for some time it was considered the largest cash transfer program in the world. There is plenty of research literature on Bolsa-Família, including studies on the global and national geopolitical context which led to its implementation, impacts of the program in reduction of poverty and inequality, analyses, and criticism of problems in management and execution, and comparison to similar programs in other countries.

Despite the fact that different studies show conflicting results regarding recent changes in poverty and inequality in Brazil, there seems to be a consensus that poverty rates have decreased considerably: official figures point to extreme poverty in 2012 being reduced to 1/7 of the 1990 figures by international standards (IPEA 2014). Bolsa-Família and other social programs (Bolsa-Escola, etc) are widely recognized for contributing to this outcome.

Brazil is also well known for another social factor that has historically compromised the wellbeing and quality of life of its citizens: crime. Fontana (2007) makes the interesting claim that up to the mid-1960s, Brazilians idealized the outlaw, endowing criminal or illegal activities “with an aura of romanticism”. In numerous cultural references (TV, films, books, theatre) the bad guy was seen as a transgressor - a hero - opposing the corrupt and incompetent established forces. This seems to have been both cause and effect of an ambivalent national view towards crime. In the ’70s, violence, and crime - particularly in the slums of Rio and São Paulo - reached previously unseen proportions, and in the ’80s, the end of the military regime brought an ideological turnaround, with a renewed popular belief in democratic institutions. Since then, intellectuals have largely abandoned the idea of a good criminal.

The global average homicide rate stood at 6.2 per 100,000 population in 2012 (UNODC 2013). Brazil has one of the highest homicide rates in the world: 25 per 100,000 in 2012, and in some regions figures currently reach over 65 per 100,000, or 1000% higher than the global average. The country has the highest years of life lost to violence out of any WHO member state.

The total cost of crime in Brazil was estimated to be R$ 92 billion in 2004, or 5.1% f GDP (Cerqueira, Carvalho, Lobão & Rodrigues, 2007, cited in Murray, Cerqueira and Kahn 2013) From 2003 to 2013, the arrest of minors for robbery and murder has jumped 138 percent in the state of São Paulo alone (NPR.org 2013). The homicide rate in Rio de Janeiro has tripled from 1970 to 1999, the rate in Porto Alegre has quadrupled in the same period, and Belo Horizonte has seen a rise of 50% a year in violent crime in recent years (Lanic.utexas.edu 1999)

Theoretical models and empirical findings have shown that poverty and inequality are major causes of criminal behavior (Loureiro 2012). The “face” of crime in Brazil is young, black, poor, and has few years of education (Murray, Cerqueira and Kahn 2013). Despite the large investment in social programs and the significant reduction in poverty and inequality in Brazil since 2003, some studies show that crimes such as robbery and theft have continued to increase, as well as non-lethal violent crimes.

This paper will look into the impacts of social programs on crime rates, with a particular focus on recent conditional cash transfer programs in Brazil. Data will be obtained from literature, government documents, international reports, and the media. The final aim is to identify if, according to current research, social programs reduce criminality, and also what are other key factors that influence crime rates in Brazil.

Literature Review

Gary Becker was the first to propose a rational criminal theory. Becker argued that criminal behavior results from a cost-benefit calculation in which the potential gains of crime are weighed against the potential costs. The cost of crime includes the nature of sanctions (fines, jail), the opportunity cost of a sanction (lost work time), and the likelihood of facing a sanction (arrest, application of sentence) (Peirce 2008). This “basic equation” has elicited a variety of approaches focused on two main pillars: decreasing the incentives (through welfare programs that reduce inequity, such as the case of Brazil) and/or increasing the deterrents of crime (increasing the perceived costs by more strict policing and penalties, such as the “zero-tolerance” policy applied in New York City in the ’80s). Pierce posits that several factors in Brazil make this basic logic too simplistic and inadequate: fast and unplanned urbanization has contributed to the establishment of large urban agglomerations where the poor are exposed to multidimensional deprivation (lack of basic public services, poor health, substandard education, inadequate housing). More than 85% of the Brazilian population lives in cities, a very high rate for an upper-middle-income country (i.e. in China urbanization rate stood at ~55% in 2014). When added to a lack of minimum income and the geographic proximity to wealthy citizens - which obviates inequality - these factors act as catalyzers to criminal behavior.

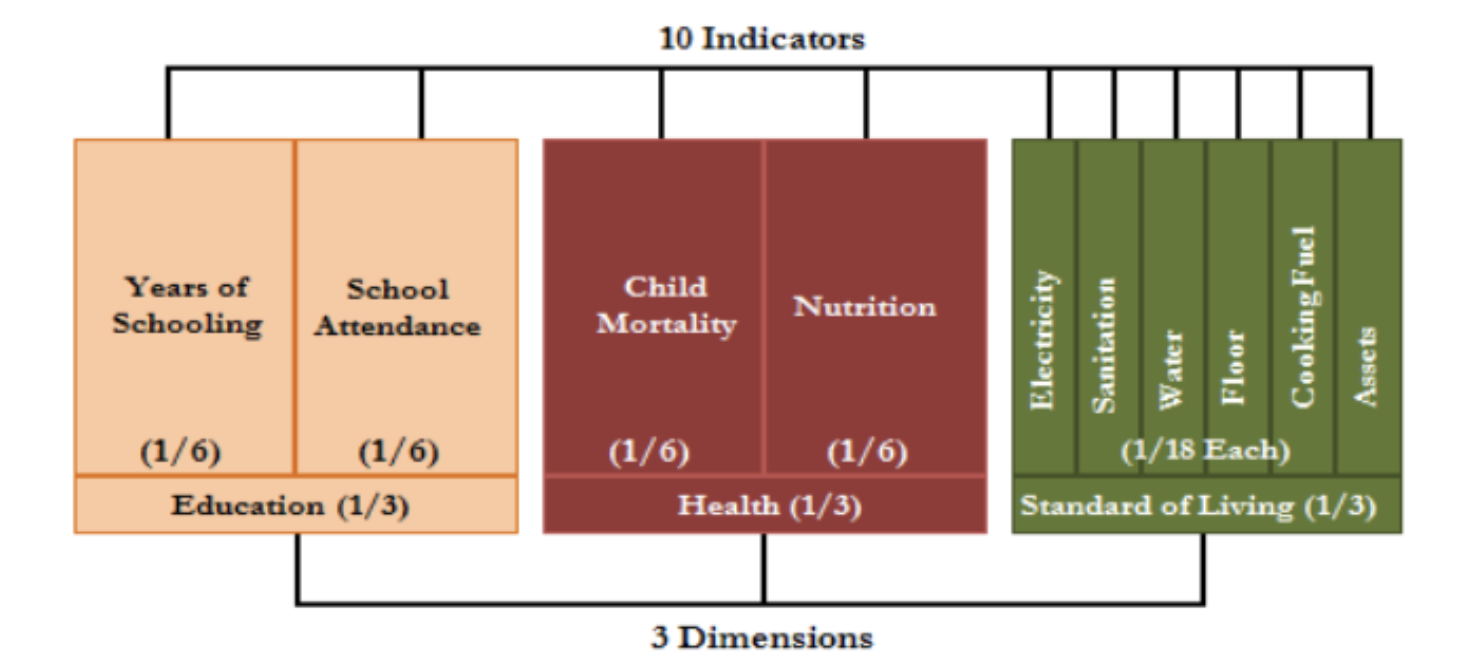

This reasoning is in line with recent definitions and techniques to measure poverty, which take into account more than just income-related aspects. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), developed in 2010 by the Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative and the United Nations, takes into account the disadvantages that a poor person experiences at the same time. In evaluating the poverty level in a household, the MPI factors in the number of years of schooling, nutrition, child mortality, as well as access to basic sanitation, drinking water, electricity and asset ownership, among other aspects (OPHI 2010). This enables policy-makers and researchers to identify overlapping deprivations and the interconnected dimensions of poverty and inequality - several of which are also conducive to crime. Karmen (1996b, cited in Bowling 1999) found that “homicide occurred overwhelmingly where there was a concentration of multiple deprivations”. When studying the rise and fall of criminality in New York City in the 1980s, Bowling found evidence that confirms Pierce’s argument that the rational criminal theory may be too simplistic when applied to large urban agglomerations:

“(…) factors outside the control of policing or governmental intervention (e.g. changes in drug-use, supply, and distribution), and non-policing interventions (e.g. community crime prevention and youth activism) may have made an equal, perhaps greater contribution to the reduction in homicide (…)” (Bowling 1999).

The ‘broken windows theory’, proposed by Wilson and Kelling (1982) provides further reasoning in this direction. Wilson and Kelling claimed that poorly maintained urban infrastructure (buildings with broken windows, litter accumulating on the pavement) generates further vandalism and anti-social behavior, leading to crime.

Several studies also point to two other aspects that may transform an environment of extreme poverty into one of routine violence: a lucrative illicit drug economy, and freely available guns. Both factors are highly relevant in the case of Brazil. The country is currently going through an “epidemic” of crack cocaine usage, particularly among youngsters in large cities (NPR.org 2013). Brazilian social scientists claim that this is closely related to the surge in urban robberies and murders committed by minors. Firearms are the main enabling factor in 66% of homicides in the Americas - the highest rate in the world (UNODC 2013).

Research Approach

This paper will try to identify relationships between cash transfer programs, poverty reduction and crime rates in Brazil by looking at data from existing literature such as the Millennium Development Goals National Monitoring Report Brazil 2014, published by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA), the 2015 Brazil Country Briefing by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (Multidimensional Poverty Index), and the Violence Map 2013 - Homicide and Youth in Brazil, by the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO).

For data concerning the effects of social programs on criminality, this paper will consider studies from several authors who analyzed national, regional, and municipal contexts in Brazil, as well as relevant cases from other countries.

By comparing evidence from the recent reduction in poverty and inequality in Brazil to official data on crime rate evolution in the last decades, and considering results from studies on the effects of social programs on crime, this paper aims at identifying potential impacts of welfare in criminality, and also shed some light on conflicting information found in different sources.

This approach is supported by further readings on the political economy of crime, and literature on social factors that contribute to violent behavior and high crime rates.

Working Hypothesis

The working hypothesis of this study is that social welfare programs have a positive impact on crime rates by reducing poverty and inequality, but there are other factors resulting from recent socioeconomic development in Brazil which contribute to growth in regional crime rates, particularly among youth in urban areas.

Results

5.1. The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are a set of eight time-bound objectives established by world leaders in 2000, as a monitoring mechanism that would enable national governments, civil society, and the international community to assess national and global progress vis-à-vis the objectives agreed at the Millennium Summit. The main problems to be addressed by the MDGs were poverty and hunger, primary education, gender equality, child mortality, maternal health, combatting HIV, malaria and other diseases, environmental sustainability, and the establishment of a global partnership for development. The Goals defined targets to be achieved in these areas by 2015, and a variety of indicators to facilitate assessment. Despite some criticism about the process that led to the definition of the Goals, as well as uneven results in different focus areas across regions, the MDGs are widely acknowledged for having renewed and focused global attention in key development issues. Progress has been made in many aspects, particularly poverty reduction, which has been reduced by 50%, ahead of the 2015 deadline.

The Brazil 2014 Millennium Development Goals National Monitoring Report presents the progress Brazil has made in working towards the United Nations Millennium Development Goals. Official figures show improvements in several indicators. Poverty has decreased significantly, in large part due to cash transfer programs such as the Bolsa-Família and initiatives like the Single Registry for Social Programs, which facilitated the targeting of social assistance. Official data places current poverty rates at 1/7th of the 1990 figures (from 25.5% in 1990 to 3.5% in 2012), according to the international poverty line of $1.25 / day (IPEA 2014).

Inequality was also reduced, with the GINI coefficient decreasing from 0.612 in 1990 to 0.526 in 2012. Despite this improvement, Brazil is still among the most unequal countries in the world. The CIA World Factbook places Brazil in 16th place among 140 countries regarding unequal income distribution (CIA.gov 2015). The reduction in poverty and inequality was accompanied by solid improvements in access to primary education (97,7% in 2012), as well as in access of the poorest 20% of the population to secondary education (from near zero in 1990 to 42% in 2012). It is also interesting to notice that access of black youth to secondary education has increased from ~10% in 1990 to 51.2% in 2012.

Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) was developed in 2010 by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) in collaboration with the United Nations as an alternative to the World Bank’s international poverty line ($1.25 per day). The MPI identifies the incidence and the intensity of poverty across three dimensions and ten indicators (Figure 1).

By considering non-income related factors in measuring poverty, such as years of schooling and access to basic public services, the MPI reflects the interconnected dimensions of poverty, allowing researchers and policy-makers to better understand specific contexts, detect overlapping deprivations and develop cross-cutting solutions. According to the MPI, a person is considered multidimensionally poor (or ‘MPI poor’) if they are deprived in at least one-third of the weighted indicators shown above (the cutoff for poverty (k) is 33.33%). The proportion of the population that is MPI poor shows the incidence of poverty, and the average proportion of indicators in which poor people are deprived is described as the intensity of their poverty (OPHI 2015). The MPI also defines that persons deprived in 20-33.3% of the weighted indicators are “Vulnerable to Poverty” and those deprived in 50% or more are living in “Severe Poverty”. People deprived in one-third of ‘severe indicators’ (e.g. practicing open defecation, walking for more than 45 minutes to get safe water, etc), are considered “Destitutes”.

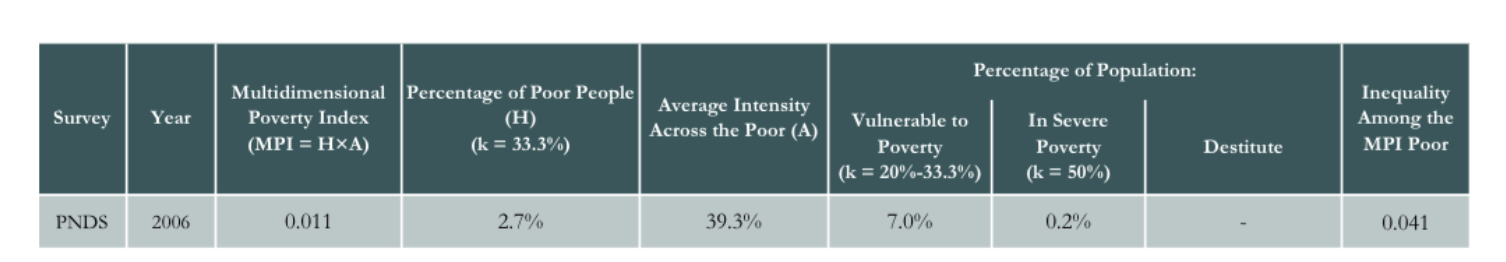

In the January 2015 Brazil Country Report by OPHI (based upon data from 2006), Brazil performs well in most areas (Figure 2). The MPI for Brazil is 0.011, while the population defined as ‘MPI poor’ stands at 2.7%. Severe poverty affects 0.2% of the population, and the index shows no destitute.

As a means of comparison, the country with the highest MPI is the Republic of Niger (0.605), where 89.3% of the population are MPI poor, 74.3% live in severe poverty and 68.8% are considered destitute. Official data from the Brazilian government states that over 40% of the population in Brazil has no access to basic sanitation, with direct negative impacts on health and quality of life. Brazil placed 112 in a recent survey of basic sanitation in 200 countries (Terra.com.br 2014). Interestingly, according to OPHI’s criteria, the population living without “improved sanitation facility” in Brazil is limited to ~1%. The reason for this discrepancy is that the MPI uses indicators established by the United Nations for the Millennium Development Goals. The UN defines ‘improved sanitation’ as “any kind of flush toilet or latrine, or ventilated improved pit or composting toilet, provided that they are not shared”, while official data in Brazil refers to the provision of clean water and collection and treatment of sewage water.

Violence Map 2013 - Homicide and Youth in Brazil (FLACSO)

The Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO) is an intergovernmental organization founded in 1957 by the Latin American States from an initial proposal by UNESCO. FLACSO’s mandate is to develop graduate education, research, and scientific cooperation in the Social Sciences, as well as support the integration of Latin American nations. The organization has currently 17 member states. FLACSO has published Violence Maps in Brazil since 1998, based on official mortality data by the Ministry of Health, as well as census data provided by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). The data is estimated to cover nearly 100% of deaths in the country.

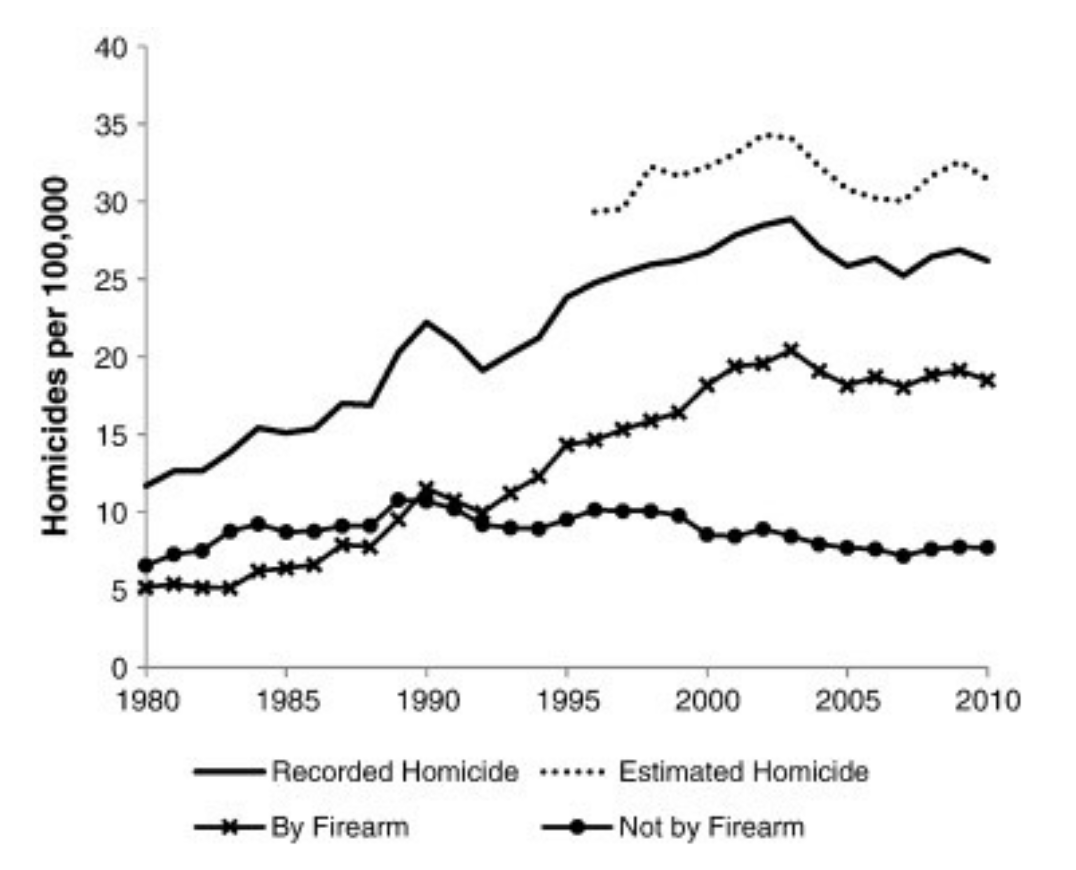

According to the Violence Map 2013, 1.145.908 people were victims of homicide in Brazil from 1980 to 2011. Homicide rates have increased steadily (Figure 3), from 11.7 deaths per 100.000 population in 1980 to 27.1 per 100.000 in 2011 (the average global homicide rate in 2012 was 6.2 deaths per 100.000). From 2004 to 2007 there was a slight decrease in homicide rates in Brazil, attributed by FLACSO to new federal gun control policies, but from 2008 rates started increasing again (FLACSO 2013).

The evolution of homicide rates among youth shows even higher figures. From 17.2 deaths per 100.000 youth population in 1980, the national rate has escalated to 53.4 homicides per 100.000 youth in 2011 (nearly twice the national average).

Regional figures show highly different rates and divergent trends. While homicide rates in the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo decreased by 67.7% and 43.9% respectively between 2001 and 2011, the North and Northeast regions have seen a surge in homicides. During the same period (2001 to 2011), homicide rates have increased by 153.1% in Maranhão, 202.3% in Paraíba, and 223.6% in Bahia. In 2011, the state of Alagoas had 72.2 deaths by homicide per 100.000 people - this is over 1000% higher than the global average and 700% higher than the rate considered ‘epidemic’ by the World Health Organization (10 deaths per 100.000 population).

Looking at youth homicide in cities, figures are shocking. Out of 27 state capitals, only São Paulo had a lower rate than the national average in 2011. In João Pessoa (state of Paraíba) youth homicide rate was 215,1 per 100.000 in 2011, and in Maceió (Alagoas), it reached 288.1 per 100.000. Rates were higher than 100 deaths per 100.000 in 10 cities.

Welfare Programs and Crime in Urban Brazil

Several studies have shown empirical evidence of the negative effect of conditional welfare programs on crime rates. By providing broad assistance and establishing rules to be followed, conditional programs raise the perceived ‘cost’ of criminal behavior, reduce the time available for criminal activities, and increase trust in society and institutions.

Loureiro (2012) notes that “the number of papers that investigate the relationship between social welfare spending and crime is more restricted and more recent than those that analyze similar issues like the effects of law enforcement on criminality”. He emphasizes that literature and evidence is even more limited for developing countries, where “the different economic environment may lead to contrasting results”.

Using a panel data of 46 countries, Pratt and Gosley (2002, cited in Loureiro 2012) found robust negative effects of social support (health care and education) on homicide.

Johnson, Kantor, and Fishback (2007, cited in Loureiro 2012) explored the effect of relief efforts in 81 cities in the United States during the great depression. The authors also found a negative effect of public welfare on crime rates (as welfare increases, crime rates decrease).

In his 2012 study, Loureiro looks at variations in the temporal implementation of Bolsa-Família in different Brazilian states as a causal factor of changes in poverty and criminality. He finds that states that implemented the program faster had a more significant reduction in poverty, and a similar - but less robust - decrease in crime, particularly robbery, theft, and kidnapping. No significant effects were found for homicide and murder rates.

Chioda et al (2012) analyzed a detailed dataset of school characteristics in the city of São Paulo from 2006 to 2009 and compared children and teenagers covered by Bolsa-Família with changes in youth crime rates in the school areas. Their estimates suggest that Bolsa-Família led to an increase of 59 students enrolled per school, and a resulting 21% reduction in youth crime in school neighborhoods. The authors mention two key factors that may contribute to this outcome: cash transfers may reduce the incentive or “need” to engage in economically motivated crimes, and welfare assistance may also alter households’ routines, affording parents more time for supervision. Other factors may include more time spent in school (less time available for criminal behavior) and improved social interactions from the changed peer group.

Peirce (2008) argues that widespread segregation (social and geographic), and the strength of illegal networks (drugs, organized crime) create an extreme and distorted urban environment in Brazil, and therefore the ‘basic equation’ of adjusting either the incentives or the deterrents for crime is inadequate and too simplistic. She posits that “non-material forms of relative deprivation are more significant than income inequality in Brazilian cities”, making policies focused on poverty alleviation and income equity insufficient for addressing urban crime in Brazil.

Murray et al (2013) conducted a systematic review of time trends and risk factors for crime and violence in Brazil. He concluded that there were large regional variations in homicide rates and trends. Until 1999, state capitals and metropolitan regions had the highest rates of homicide. Since then, however, rates stabilized in those areas and there has been a consistent growth trend in smaller cities and countryside regions. The authors reviewed literature discussing many possible causes of high homicide rates in Latin America, including colonization patterns by the Portuguese and Spanish, slavery, and military dictatorships.

Cerqueira (2010, cited in Murray et al 2013) developed a set of seven national indicators of socioeconomic changes between 1980 and 2007 and related them to homicide trends. The indicators were national income, inequality levels (GINI index), the proportion of young males in the population, firearm availability, use of illegal drugs, police numbers, and rates of incarceration. Changes in these variables explained about two-thirds of the variation in homicide rates between 1980 and 2007. The most relevant factors were the growth in inequality, the increased availability of firearms, and the rise in drug use.

Finally, Imbush, Misse, and Carrión (2011, cited in Murray et al 2013) suggest that growing homicide rates in Brazil since the 1980s resulted from a combination of “increased inequality, disorganized urbanization, availability of firearms, weak social institutions, and drug trafficking, together with cultural characteristics, and democracy that guarantees political but not social rights”.

Conclusion

The first observation from an initial literature review on the relationship between social programs and crime rates in Brazil is that there seems to be a lack of detailed, reliable national data on criminality, compatible with international standards. National-level victimization data is not detailed enough and reports do not fully comply with international reporting practices, which creates problems in making the available research internationally comparable. Also, as most of the data is available in Portuguese only, international researchers have difficulty in accessing these figures. Nevertheless, governmental agencies, as well as several other reputable institutions, do publish annual official reports, and researchers as well as international organizations have made use of these sources to try to analyze the Brazilian context and compare it to global data.

A second observation is that crime in Brazil is a complex issue. National statistics do not clearly represent regional figures or trends, which are highly influenced by changing social factors such as usage of illicit drugs and availability of firearms, as well as by significant differences in the availability of - and access to - basic infrastructure and public services.

Several studies show that Bolsa Família has reduced poverty - and in less scale, also inequality - in Brazil. Nevertheless, inequality rates are still very high when compared to international figures.

Welfare programs seem to have a negative impact in criminality, particularly property-related crimes. This seems to be true also in relation to youth crime, as evidenced by studies in school neighborhoods.

However, there are non-income-related factors that exert a strong influence in crime rates and may decrease impacts of welfare programs on criminality, namely firearm availability, use of illegal drugs, the proportion of young males in the population, urbanization patterns, social rights and strength of social institutions, police numbers, among other.

Crime rates have consistently increased in Brazil in the last three decades, and homicide rates have shown very high growth, particularly among youth in less developed states and cities in the North and Northeast. The “face” of crime in Brazil is still predominantly young, black, poor, and with few years of schooling. Some of the regions where youth crime has shown high growth are also suffering from the widespread use of crack cocaine.

Violence and crime trends show that criminality growth is moving towards less developed states, smaller cities, areas with weak policing, and regions where drug use is more prevalent (North and Northeast).

Based on results from the studies analyzed for this paper, one can conclude that recent social programs such as Bolsa Família in Brazil have contributed to reducing poverty and inequality, and also had a negative impact in crime rates in specific contexts and regions in Brazil, mostly when associated with other policies such as capacity building, gun control and better policing. However, systemic problems like weak institutions and disorganized urbanization, coupled with dynamic social aspects like an increase in drug usage and firearm availability, have hampered progress in crime reduction, particularly in less developed cities and states. Therefore, apart from efforts in social assistance, crosscutting policies are needed in order to reinforce the capacity of public institutions, improve urban planning and management, increase police effectiveness, and tackle illicit drugs and access to firearms.

Bibliography

Bowling, B. 1999. 'The Rise And Fall Of New York Murder: Zero Tolerance Or Crack's Decline?'.British Journal Of Criminology 39 (4): 531-554. doi:10.1093/bjc/39.4.531.

Cia.gov. 2015. 'The World Factbook'. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2172rank.html.

Chioda, Laura, João de Mello, and Rodrigo Soares. 2012. 'Spillovers From Conditional Cash Transfer Programs: Bolsa Família And Crime In Urban Brazil'. Discussion Paper Series, Forschungsinstitut Zur Zukunf Der Arbeit N. 6371.

FLACSO. 2013. Mapa Da Violência 2013.

Fontana, M. 2007. 'Plunging Into The Underground: Poverty And Violent Crime In Contemporary Brazil'. Asia Pacific Media Educator 18: 72-84.

IPEA. 2014. Objetivos De Desenvolvimento Do Milênio - Relatório Nacional De Acompanhamento.

Lanic.utexas.edu. 2015. 'Rising Violence And The Criminal Justice Response In Latin America'. http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/etext/violence/memoria/.

Loureiro, Andre. 2012. 'Can Conditional Cash Transfers Reduce Poverty And Crime? Evidence From Brazil'. SSRN Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2139541.

Murray, Joseph, Daniel Ricardo de Castro Cerqueira, and Tulio Kahn. 2013. 'Crime And Violence In Brazil: Systematic Review Of Time Trends, Prevalence Rates And Risk Factors'. Aggression And Violent Behavior 18 (5): 471-483. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.003.

NPR.org. 2013. 'As Youth Crime Spikes, Brazil Struggles For Answers'. http://www.npr.org/2013/04/30/180067497/as-youth-crime-spikes-brazil-struggles-for-answers.

OPHI. 2010. The Multidimensional Poverty Index And & The Millennium Development Goals: Showing Interconnections.

OPHI. 2015. OPHI Country Briefing January 2015: Brazil.

Peirce, J. 2008. 'Divided Cities: Crime And Inequality In Urban Brazil'. Paterson Review 9: 85-98.

Terra.com.br. 2014. 'Brasil É O 112º Em Ranking De Saneamento Básico Mundial'. http://noticias.terra.com.br/brasil/brasil-e-o-112-em-ranking-de-saneamento-basico-mundial,4db28c72d36d4410VgnCLD2000000ec6eb0aRCRD.html.

UNODC. 2013. Global Study On Homicide.

UNU-WIDER. 2014. Is There A Brazilian Model Of Development?.