Lowering carbon emissions from anthropogenic activity is a key priority of the international community towards mitigating climate change in the 21st century. Land-use change accounts for a significant part of global emissions - 14-20% from 2000 to 2007 (Arima et al 2014), mostly from deforestation of tropical forests. Brazil holds approximately 1/3 of the world’s tropical forests, with 463 million hectares of land - 54% of the national territory - occupied by rainforests (90% of which are located in the Amazon region) (IFB 2013). In the last decade, deforestation in Brazil peaked in 2004, when nearly 30.000 Km2 of forest area was destroyed. According to the Brazilian government’s Second National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), 77% of Brazil’s carbon emissions from 1990 to 2005 came from the land-use change and forestry sector (LUCF), with 67% of this total originating in the Amazon region and 22% in the Cerrado (MCTI 2010). Brazilian forests have the largest global carbon stock in living forest biomass (62.6 billion tons) (IFB 2013). These figures highlight the importance of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon region as a global source of carbon emissions, and Brazil’s significant role in climate change mitigation.

For most of the 20th century, deforestation in Brazil seemed to be an intractable problem: inadequate data, poor enforcement of public policies, and an inefficient land tenure system, as well as growing global demand for meat, soy, and forest products, contributed to increasing levels of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, mainly in the states of Mato Grosso and Pará. Considering the impact of deforestation on carbon emissions, Brazil seemed to be heading towards a questionable future regarding climate change mitigation.

The 2000s brought a very different scenario. Improved monitoring, smarter and stricter policies, powerful advocacy, several market interventions, and international financing led to a sharp decrease (over 70%) in deforestation in Brazil from 2004 to 2012. As a result, 3.2 billion tons of CO2 were kept out of the atmosphere, making Brazil the current (2015) world leader in climate change mitigation. Adding to this achievement, the reduction in deforestation and emissions happened while the production of beef and soy continued to rise, making this an interesting and rare case where significant environmental protection and emission reduction were achieved alongside economic growth.

These achievements are currently under threat, as deforestation rates have increased by 30% in 2013, and by over 450% in some months of 2014, when compared to the same period in the previous year (Imazon.org.br 2014).

This study will look into the recent surge in deforestation in Brazil. The author will analyze previous interventions that contributed to the decrease in deforestation and carbon emissions, identify new factors that are compromising this achievement, and discuss how current political turmoil may amplify this negative trend by deepening institutional vulnerability.

Reduction in Deforestation in Brazil 2004 - 2012: Context, Interventions, and Outcomes

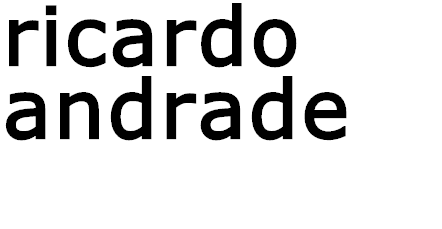

Nepstad et al (2014) propose a detailed analysis of the context and interventions that led to a decline of over 70% in Amazon deforestation from 2004 to 2012. In Figure 1, the authors present the variation in annual deforestation rates from 1994 to 2013 against the percentage of the Brazilian Amazon allocated to different land uses: agrarian reform settlements, demarcation of indigenous territories, and forest areas that were strictly protected and sustainably used.

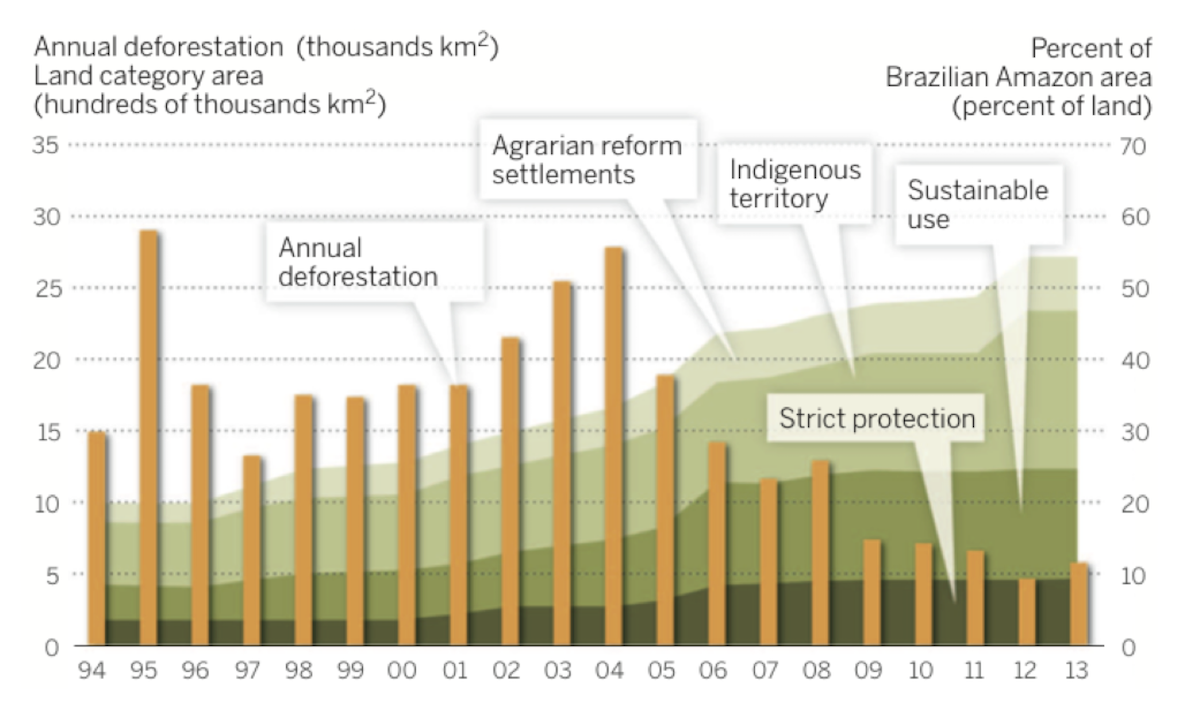

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of soy and beef production and respective yields in Brazil during the same period (1994 - 2013). As one can see, while conservation and land tenure policies improved consistently during the period considered in this study, the greatest improvements matched the period of sharp decrease in deforestation (2004 - 2012). It is also interesting to note that, with the exception of the period 2005-2007 (when the soy moratorium was in effect), production and yields of soy and beef continued to grow while deforestation was in decline, demonstrating sustainable growth with reduced deforestation and carbon emissions.

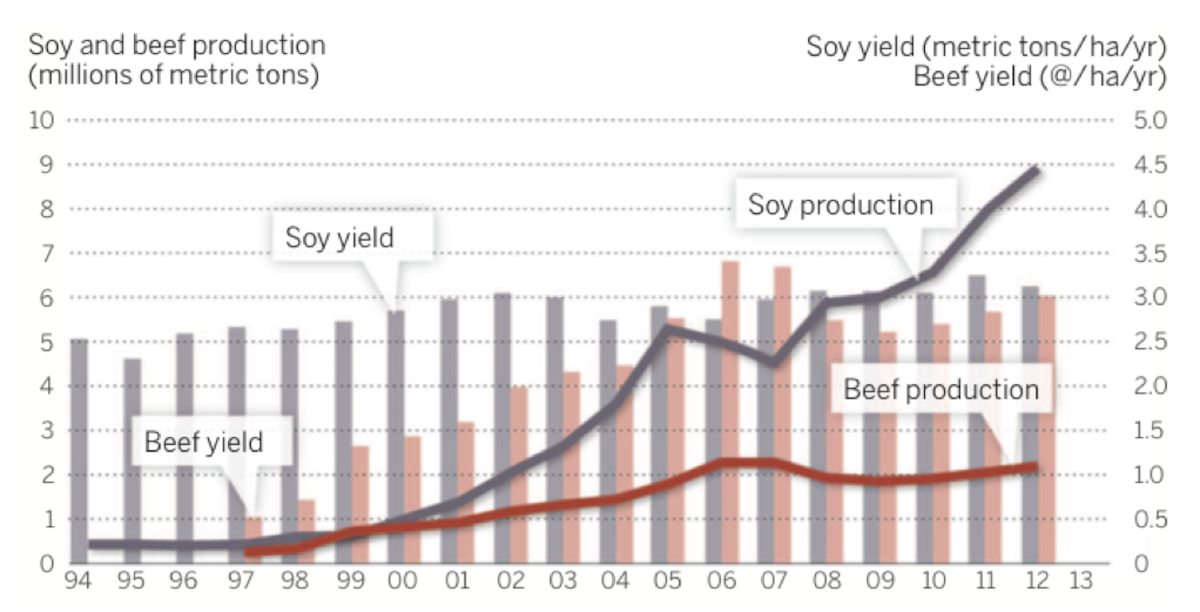

Nepstad et al describe three phases of recent deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, namely agro-industrial expansion, frontier governance, and territorial performance. Figure 3 provides a clear view of the context and main interventions during each phase.

The first phase, agro-industrial expansion, took place in the early 2000s as a result of the surge in the price of commodities in the international market in the 90’s. High profits led to a strong expansion of soy and cattle activities in the states that border the Amazon region (mainly in Mato Grosso). Protected areas were mostly in remote regions of the Amazon, far from where deforestation was happening, and the Forest Code - the main Brazilian forest legislation - which at the time required landowners in forest areas to preserve 80% of the original vegetation, was not enforced. At that time there was no national database of rural properties - the first state-level initiative was launched in Mato Grosso, but registration happened at a slow pace.

The second phase, frontier governance, was marked by a very different international context, as well as by several simultaneous policy, advocacy, and market interventions, which were highly successful in curbing deforestation. From 2005 through 2006 soy and cattle prices plummeted, making these activities less profitable for farmers. Meanwhile, the Brazilian government launched the Plan for the Protection and Control of Deforestation in the Amazon (PCDDAm), which elevated the issue to the President’s office, empowering the Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministério Público Federal) and the Federal Police, and involving them in coordination. The technology was also updated with the DETER System (Detection of Deforestation in Real Time), policies were locally enforced, and protected areas grew rapidly with strong political commitment as well as with the launch of the Amazon Region Protected Areas Program. In 2006, a Greenpeace-led moratorium on the Amazon soy industry was joined by most buyers of local soybeans: farmers who grew soy on land cleared after 2006 could not sell anymore to participating buyers. This concerted effort led to an initial drop of nearly 50% in Amazon deforestation.

Figure 3. Phases of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon 2000-2013. Nepstad et al (2014)

In the third phase described by Nepstad et al, territorial performance, monitoring, and enforcing of conservation policies focused on districts and counties, increasing accountability of mayors, local public officers, and farmers within critical areas. Collaboration between the Central Bank and the Ministry of the Environment led to the establishment of the Critical Counties Program, which suspended access to agricultural credit for farms and ranches located in the 36 counties with the highest deforestation rates. As a result, local communities united to address deforestation, which decreased drastically in 11 counties. Apart from coercive measures, some states launched positive incentive programs, such as the Green County Program in Pará, which provided support to critical counties that wished to get off the “blacklist” and regain access to credit. In 2008, Brazil launched the National Plan on Climate Change (PNMC), with the goal of reducing deforestation by 80% until 2020. In the same year, the second phase of the PCCDAm was launched, leading to the intensification of field inspections and the embargo of properties which allowed deforestation. A US$ 1 billion, performance-based pledge by Norway helped create the Amazon Fund, supporting the expansion of protected areas and other initiatives in the region, while several states started preparation to establish regional REDD+ legislation. In 2009, Greenpeace started a new campaign that resulted in the “Cattle Agreement”, by which cattle raising farmers in the Amazon region who deforested after 2009 were excluded from the supply chain of the largest beef processing companies. In 2012 the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture launched a US$ 1.4 billion preferential credit line for farmers complying with environmental laws, and in 2013 the Norway-Brazil agreement was extended to 2021.

The three phases of recent Amazon deforestation described above show that, during a relatively short period of time, the interaction of several mutually reinforcing interventions at different levels, in the public and private sector, as well as strong advocacy by NGOs and civil society, provided both effective coercive measures as well as positive incentives to farmers and landowners who followed environmental legislation. This combination of factors led to a decrease of over 70% in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon from 2004 to 2012, establishing Brazil as a world leader in the reduction of carbon emissions and climate change mitigation.

A New Scenario and the Impact of Political Transition

Despite Brazil’s success in reducing deforestation while maintaining growth in the last decade, recent factors threaten to potentially reverse this achievement. A significant drop in international commodity prices has led Amazon farmers to start a strong lobby for the Forest Code (FC) to be altered. In 2012 President Dilma Rousseff approved a new version of the law, granting amnesty to all farmers and landowners who had deforested before 2008. This has created an atmosphere of impunity: according to Philip Fearnside, a Research Professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon (INPA), “(…) the expectation now is that if you violate the law and cut down the forest without a permit, you’ll eventually be pardoned” (New Scientist 2015).

In 2013 Amazon deforestation increased by 30%, in what Fearnside defines as an expected “hiccup” after the sharp reduction in previous years. From September 2014 to January 2015, deforestation rates more than doubled compared to the same period in the previous year, and in October 2014 there was an increase of 467% compared to October 2013 (Imazon.org.br 2014).

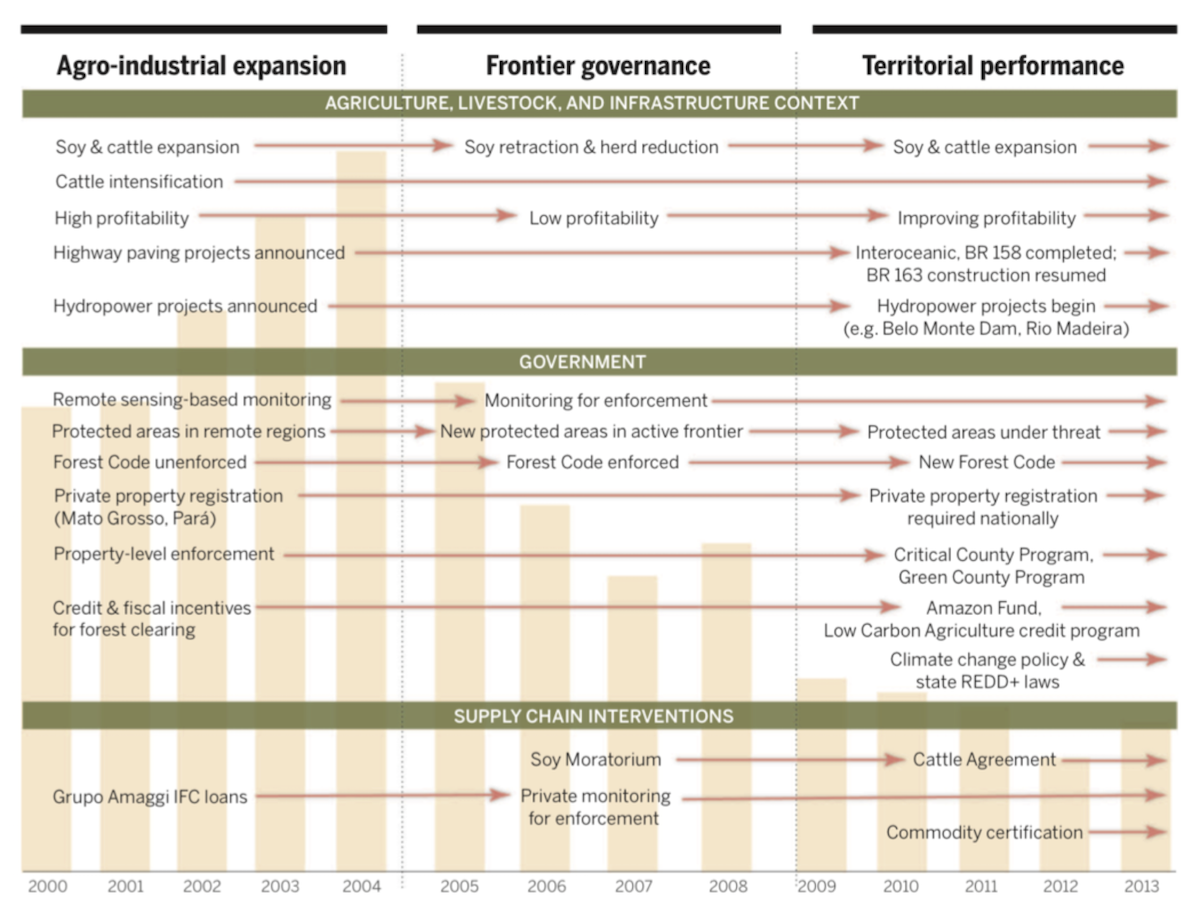

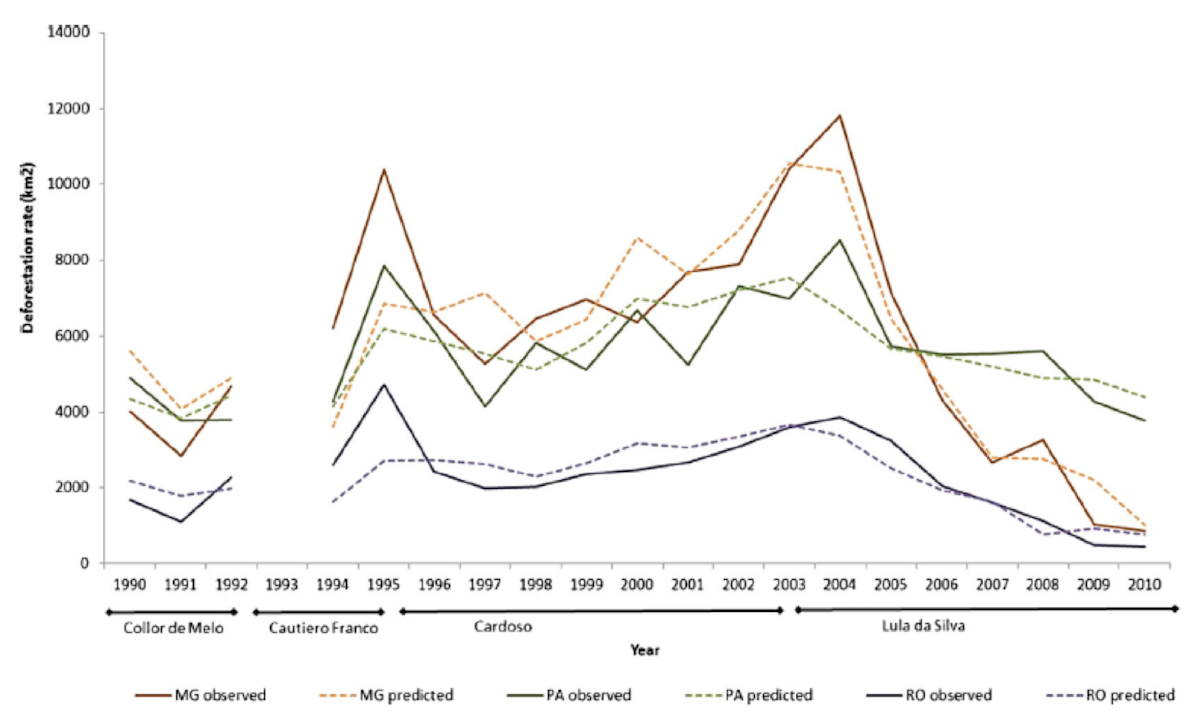

Apart from well-known drivers of deforestation such as international commodity prices, exchange rates, land reform, migration, roads, and infrastructure projects, a study by Rodrigues-Filho et al (2014) draws the attention to the relevance of institutional dimension in planning models, and particularly of political transitions. By constructing ARIMA models for the prediction of deforestation in eight Amazon states and comparing the predictions with real deforestation data for 1990 - 2010, the authors found that during the two “peaks” of Amazon deforestation (1995 and 2003-2004) the actual rates were consistently over 50% higher than the predictions (Figure 4). These peaks occurred on the first years of the first terms of the two Brazilian presidents elected since 1994 (Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Luís Inácio Lula da Silva). By contrast, there was no significant change in deforestation rates when elections led to no administrative change. The authors argue that these results point to a new predictor of deforestation in Brazil: political transition and the consequent administrative instability.

FIGURE 3. Observed and predicted deforestation using ARIMA, and political transitions. Rodrigues-Filho et al (2014)

Discussion

The 2014 presidential elections in Brazil were the most disputed in the country’s recent political history, with Dilma Rousseff winning by a very small margin of 3.28%. Up to the last minute before the second turn of the election, most surveys showed no clear favorites, which led to an atmosphere of high political uncertainty.

Fearnside (Schiffman 2015) claims that the Rousseff administration hid recent official deforestation data until after the 2014 elections in order to avoid political damage. August and September 2014 data should have been released by October, but it was not disclosed until the end of November (the second turn of the election was held on 26 October).

October 2014 was also the month with the highest growth in deforestation rates since the reduction trend was reversed: rates were 467% higher than the same period in 2013 (New Scientist 2015).

In December 2014, recently re-elected President Dilma Rousseff added to the scenario of environmental uncertainty by appointing Senator Katia Abreu, known by environmentalists as “Chainsaw Queen” (Watts 2014), to the Ministry of Agriculture, and former congressman Aldo Rebelo, who has claimed that “global warming is incompatible with current knowledge”, to the Ministry of Science and Technology (Tegel 2015).

The heated political transition in the 2014 presidential elections, as well as the uncertainty towards future environmental policies with the two new controversial appointees to the presidential cabinet, along with the recent spike in Amazon deforestation, seem to reinforce the results obtained in the study by Rodrigues-Filho et al. The authors argue that in order to reduce institutional vulnerability in combating deforestation during political transitions, staff turnover needs to be reduced and meritocratic criteria must be applied to more than 20.000 administrative positions subject to clientelistic appointments at the federal level. Despite administrative modernization in specific areas of the public sector since the early 2000s (i.e. social protection programs such as Bolsa-Família) and recent promises by the Rousseff administration of political reform (including a drastic potential reduction in the number of ministries as a way of improving public approval ratings), federal appointments are an essential element of the Brazilian political system, traditionally based on coalition-building. Furthermore, a strong conflict between Congress and the Rousseff Cabinet, along with a negative economic outlook and ongoing large-scale corruption scandals have corroded political stability and may lead to the impeachment of President Rousseff or to new elections in the coming months. If this is confirmed, and taking into account Verburg et al’s findings, one could foresee a bleak scenario for the Amazon forest in 2015, with a considerable increase in deforestation rates.

Conclusion

This paper has analyzed some of the main factors that led to a sharp reduction in deforestation and carbon emissions in Brazil from 2004 to 2012 and discussed how a new political context may compromise and potentially reverse the results achieved so far.

Apart from the effects of traditional drivers of deforestation, recent studies have demonstrated the negative impact of political transitions in deforestation rates in the Amazon. The last presidential elections in Brazil in 2014 have coincided with a new surge in Amazon deforestation, reinforcing previous findings that showed similar peaks during administrative shifts in 1995 and 2004.

The author argues that current political instability in the country points to a continuous increase in deforestation in the near future, based on Rodrigues-Filho et al’s findings. Additionally, expectations of meritocracy and lower turnover in federally appointed positions - which could decrease institutional vulnerability - are not realistic in the present context, considering that the Brazilian political system is traditionally based on coalitions, requiring the government to use political appointments to negotiate with Congress and maintain political support.

Bibliography

Arima, Eugenio Y., Paulo Barreto, Elis Araújo, and Britaldo Soares-Filho. 2014. 'Public Policies Can Reduce Tropical Deforestation: Lessons And Challenges From Brazil'. Land Use Policy 41: 465-473. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.06.026.

IFB. 2013. Brazilian Forests At A Glance. Instituto Florestal Brasileiro.

Imazon.org.br. 2014. 'Imazon | Categorias Forest Transparency'. http://imazon.org.br/categorias/forest-transparency/?lang=en.

MCTI. 2010. Second National Communication Of Brazil To The United Nations Framework Convention On Climate Change. Ministério de Ciência Tecnologia e Inovação.

Nepstad, D., D. McGrath, C. Stickler, A. Alencar, A. Azevedo, B. Swette, and T. Bezerra et al. 2014. 'Slowing Amazon Deforestation Through Public Policy And Interventions In Beef And Soy Supply Chains'. Science 344 (6188): 1118-1123. doi:10.1126/science.1248525.

New Scientist. 2015. 'Amazon Deforestation Soars After A Decade Of Stability'. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn27056-amazon-deforestation-soars-after-a-decade-of-stability/.

Rodrigues-Filho, Saulo, René Verburg, Marcel Bursztyn, Diego Lindoso, Nathan Debortoli, and Andréa M.G. Vilhena. 2015. 'Election-Driven Weakening Of Deforestation Control In The Brazilian Amazon'. Land Use Policy 43: 111-118. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.11.002.

Schiffman, Richard. 2015. 'What Lies Behind The Recent Surge Of Amazon Deforestation By Richard Schiffman: Yale Environment 360'. E360.Yale.Edu. http://e360.yale.edu/feature/what_lies_behind_the_recent_surge_of_amazon_deforestation/2854/.

Tegel, Simeon. 2015. 'Brazil's Cabinet Now Has A Climate Change Denier And A 'Chainsaw Queen''.Globalpost. http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/regions/americas/brazil/150110/brazilian-government-climate-change-denier-deforestation.

Watts, Jonathan. 2014. 'Brazil's 'Chainsaw Queen' Appointed New Agriculture Minister'. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/24/brazil-agriculture-katia-abreu-climate-change.